In the summer of 2021, Arizona Republic investigative reporter Caitlin McGlade found out that Joann Thompson had been severely beaten by another resident at Bethesda Gardens Assisted Living facility in Phoenix.

Most reporters would have written Joann’s story right then, and it would have been compelling.

But McGlade had been covering the senior living industry since the early days of the pandemic, and she wondered whether the assault at Bethesda Gardens was a solitary event or if there was something more widespread going on.

She had just finished a series of stories about how Granite Creek Health and Rehabilitation Center in Prescott had hired a man with a felony conviction on his record to run the facility, how he forced employees to continue to work even though they were sick with COVID-19, and how 15 residents died.

McGlade knew that both of the organizations charged with regulating nursing homes and assisted living facilities, the Arizona Department of Health Services and the Arizona Board of Nursing Care Institution Administrators and Assisted Living Facility Managers, had been criticized in audits for not doing enough to protect seniors.

So she decided to dig into the subject of resident-on-resident harm to find out how often residents were hurting each other.

Her first calls were to plaintiff attorneys who confirmed that the issue was an important one and not well-known outside of families whose loved ones had been injured.

She then asked the Arizona Department of Health Services if facilities like Bethesda Gardens have to report assaults to the state. As it turns out, Arizona law does not require assisted living facilities to report all resident injuries to the health department.

The next step was to review stories written by newspapers across the country. There were a few notable articles, including a standout series in the Minneapolis Star Tribune.

It was through that research that McGlade came across Eilon Caspi, a researcher based at the University of Connecticut, who wrote a book about conditions that lead residents to hurt one another.

Caspi told McGlade that the problem was widespread, that it was generally caused by neglect in the facilities, that the industry viewed seniors hurting each other as inevitable and had taken to labeling them as “aggressive.”

But how would she find out how many seniors were being hurt in Arizona?

The only solution was to turn to police reports.

McGlade first requested police call histories from every nursing home and assisted living facility in the state that serves more than 10 people. She then requested incident reports for calls stemming from assaults, domestic violence, fights, sex offenses and abuse, and variations of those keywords.

With help from other reporters at The Republic, McGlade spent nine months building a database that documented alleged or substantiated physical contact between residents, or between residents and facility employees. Team members listed information like times, dates, locations, medical diagnoses and other factors in order to determine where and how seniors were hurting each other across the state.

Though Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services keeps organized data chronicling nursing home citations, there is no label for resident-on-resident harm-related deficiencies. So counting the total number of these cases — and where they happen around the country — is nearly impossible.

To find nursing home citations for resident-on-resident harm in Arizona, reporters filtered federal data for a variety of citation types that might include resident-on-resident harm, downloaded the 200-plus corresponding reports and searched them for keywords such as altercation, aggressive, hit, punch, kick and more. Some reports were not text-searchable, so reporters read those.

Reporters found fewer than 50 references to resident-on-resident harm out of about 1,500 citations, but there may be more in reports not included in their sample.

They also added to the database by reviewing hundreds of state citation reports on nursing homes, which have to report resident injuries to their licensing agency.

Once that was done, McGlade and fellow reporters interviewed families, attorneys, facility employees, facility directors and researchers over the course of seven months to deepen their understanding of what they were seeing in the data.

Resident-on-resident harm typically comes up in the news as short, breaking stories. The Republic’s series is different because it seeks to deepen the public’s understanding of a complex, systemic problem facing seniors, their families and the people who are paid to take care of them.

Joann is not alone.

Science

Early in the reporting process, researchers told reporters that senior living residents who hurt each other commonly suffer from dementia and related conditions. So the team set out to understand how dementia affects the brain, how those brain changes in turn affect behavior and why scientists have yet to find a cure for the disease.

Melina Walling had covered bioscience for The Republic for several months when she started working on this project. Her reporting on COVID-19 had led her to an obsession with the immune system, culminating in a multipart series on latent viruses and the hidden impacts they may have on health.

After that series, she understood that scientists might have different approaches to a puzzle as challenging as dementia and Alzheimer’s. So she started reading and researching. She read Caspi’s book, "Understanding and Preventing Harmful Interactions Between Residents with Dementia," listened to pertinent podcasts and read dozens of articles on the topic.

She soon realized that scientists were considering many different hypotheses, and she would need to talk to a wide range of people to understand them.

To try to get at the big themes in the research, Walling talked to experts who have worked at Arizona’s three major universities: Arizona State University, the University of Arizona and Northern Arizona University. She read research papers, examined trends in research topics over time and kept abreast of new publications in research and drug development, many of which are still ongoing.

Finally, the team visited one researcher’s lab in person. They held a human brain and looked at brain tissue samples with Diego Mastroeni, a professor at ASU. That turned out to be a perfect stepping stone for illustrator Emily Nizzi to start thinking about visuals.

Illustrations

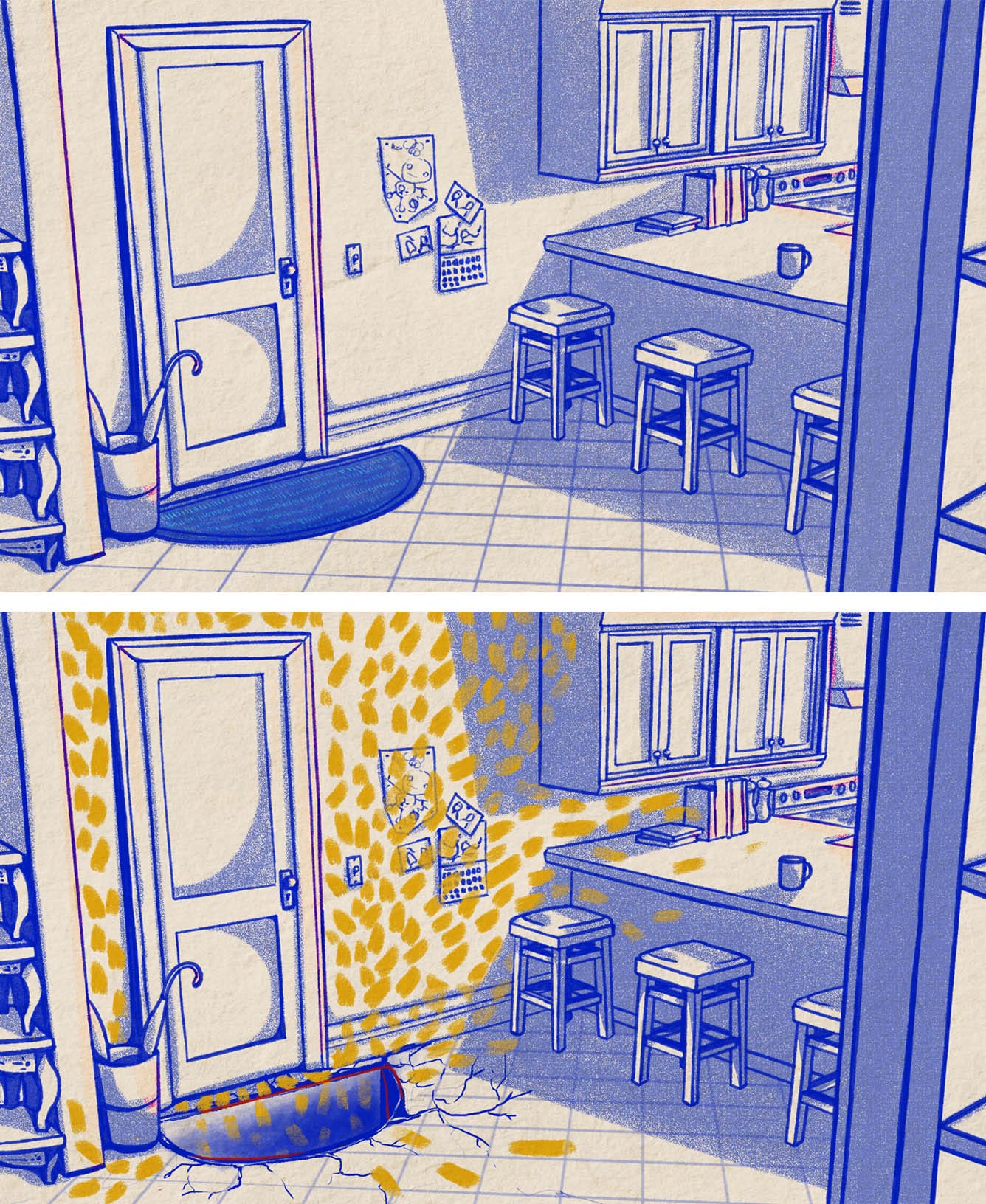

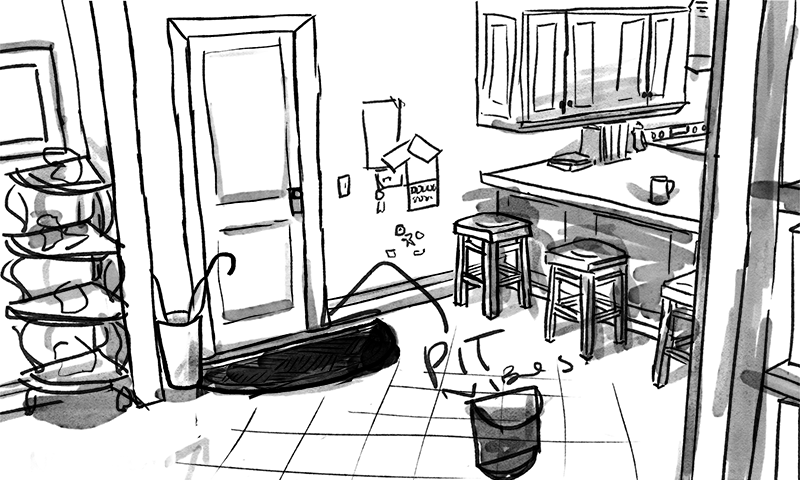

Nizzi said that her first impressions of the project were of the fear and helplessness that everyone — from residents to family members to staff — must move through while navigating dementia care.

To combat helplessness with knowledge, Nizzi illustrated the biology of the brain with the help of resources from the Alzheimer’s Association. She entered a series of ongoing conversations with Mastroeni about drawing neurons, amyloid plaques and more in a simple design for a general audience.

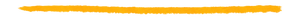

Based on Walling’s conversations with Lori Reynolds, a gerontology expert, Nizzi knew that there was potential for illustrating how someone’s understanding of the world could be altered by Alzheimer’s and how that could pose challenges for caregivers.

Nizzi decided to represent those changes not only by how they manifest in the body, but also as color, texture and movement. She pitched an aesthetic that she described as frenetic, surreal and almost psychedelic, to express anxiety. She knew from the start that a vibrant but oppressive blue would serve as an anchor for the series of images.

From that point on, the team had several conversations about what specific elements of the story would be best expressed visually and how, with an emphasis on dignity and respect for people with dementia and other conditions. Working with Reynolds, Nizzi showed what could be briefly terrifying or unsettling for someone who cannot make sense of the world around them. She sketched, discussed and brought designs back to the drawing board with Reynolds’ expert opinion in hand.

Finally, Nizzi created illustrations for the rest of the stories, working in elements of each narrative and building on the cohesive style she had designed throughout the project.

Financials

Staffing is a major cost for senior care facilities and is critically important for quality care. So The Republic set out to find out how nursing home ownership affects staffing levels and what happens when facilities are understaffed.

Through a series of conversations with Charlene Harrington, professor emerita of sociology and nursing at University of California San Francisco, the team began to understand the complex relationship between facility ownership, profits and losses and staffing. Research papers, reports from industry advocates and critics, publicly available financial statements and source interviews gave reporters a nuanced picture of the challenges nursing homes face hiring staff and the business practices employed by their owners.

Sahana Jayaraman, an investigative data reporter at The Republic, dove into federal nursing home data to understand what nursing home staffing levels and costs look like today.

She analyzed the day-by-day staffing data published by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for each nursing home over five years – more than 20 million rows of data.

She compared Arizona and national nursing home staffing levels to thresholds under which nursing homes were more likely to have quality issues for long-stay residents, established by a 2001 study for CMS. Beginning with a methodology developed by the team at USA TODAY for their Dying For Care project, Jayaraman created an analysis for the Republic’s purpose: to find out how many nursing homes met the recommended minimum staffing thresholds across every year.

Jayaraman then tackled the annual cost report information nursing homes are required to file with CMS. She analyzed 2021 financial data, poring over CMS documentation, provider enrollment forms, and electronic reporting specifications to figure out how many nursing homes reported profits from the services they provide to residents.

Dedication

We would like to dedicate this project to our sources who courageously shared their stories; to our team members’ loved ones who have suffered from Alzheimer’s and dementia; and to all our readers whose lives have been touched by this issue. You are not alone.

Caitlin.Mcglade@arizonarepublic.com, Melina.Walling@azcentral.com, sjayaraman@gannett.com